Breaking 4:00:00 at GFNY

by Chris Geiser

…and so the glove was dropped on the George Washington Bridge. Not a cycling glove mind you. A gauntlet. As in the “gauntlet has been dropped”, old school. The challenge has been issued, and both the chase, and the speculation, are already on. Now in it’s ninth year, there has never been a sub-four-hour finish (gun time), in a GFNY Championship NYC race. With elite racers coming from all over the world to try their hand at one of the world’s most brilliantly cruel courses, the phrase “four and change” has become de rigueur on the GFNY podium in Fort Lee. And so now it is officially on.

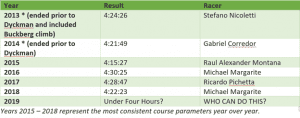

Reference table of the past winners of GFNY Championship NYC and the winning times. While these racers have gotten close, there is yet to be a racer who has broken the four hour mark.

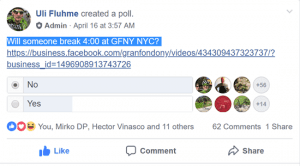

On April 16, 2019 at 3:57 AM — a poll was published on social media:

The challenge laid out on Facebook — an overwhelming “NO” vote as of April 24. Your humble servant here was among the “NO” votes.

The early days of the poll revealed an overwhelming “No” response to the question posed. But what of the reason for the question. Clicking through, a video revealed that GFNY is offering a $10,000 prize for anyone that can finish the race in under 4:00:00 (meaning 3:59:59 is the first qualifying time), and that this rider must be the overall winner of the race. With the four hour mark within 15 minutes in 2015, and an average time of 4:24:16 over the past four races, why the overwhelming no? Is it because twenty-four minutes is an absolute eternity in cycling? Is it the course? The time of year? Why would the four-hour mark elude us for so long?

Where were the experts in all of this? 62 comments revealed a combination of racing gallows humor, and some pretty strong opinions from race handicappers all over the globe, but with only a few opinions from racers that thought that they could top the mark. With my sense of Gonzo journalism absolutely piqued, I just had to know more about what would go into making this work. But where to start?

Starting at the Source

Understanding the challenge was as easy as asking the team that put the challenge forth. So I went to Uli Fluhme, CEO of GFNY and laid it on the line — what’s the inspiration? And why now, I asked. “I think it’s pretty straight forward if you have the talent at the start” he said, “if you have a few guys not playing tactics too early.” Hmm, elusive, he tests me with his riddles and cryptic advice. I started to translate this into something that would help my bookie’s brain parse it into a prediction. So, the right racer, not taking the course for granted, and not playing games with each other, may have a chance of staying away and doing something very special. If you have ridden the GFNY course, you know, go too hard, too early, and you will ruin your chances when the hard work begins. Playing cat and mouse on the way to Bear, will force you to burn matches that may cost you. But hey — like I said, I am speculating here, and I am doing it as a 52-year-old amateur with aspirations for a finishing time that the winners of this race generally associate with their third plate of post-massage pasta.

Meet the Experts

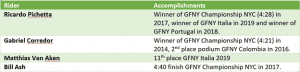

Really unpacking what this would take would mean talking to people that have the best shot at making it a reality. I was lucky enough to be able to get in touch with a who’s who of GFNY accomplishments in the realm of finishing fast, to see what it would look like to make it all work. Let’s meet the experts:

The riders interviewed for this article and their accomplishments.

I would say that this group is pretty well qualified to talk about the time range. Wouldn’t you?

Let’s Unpack

To be an elite bike racer you must be something of an optimist. You must know what it takes to dig deep and turn yourself inside out to achieve a result. When I had first heard that this challenge was happening, all I could think of was watching one of the pro teams leaving the gate on a team time trial, nine riders pedaling as if they were one, establishing a pace, rotating with discipline, and crossing the line (those who didn’t crack under the pressure of the strongest rider), as a group achieving a time that no one of them could achieve on their own. Racing against the clock — the motivation of it. Racing as a team — the tactic. But what of the others on the course? Simple. There is absolutely nothing to be done about the performance of another team in a team time trial. It’s out of your control. But on the GFNY course — the other racers are there. Testing you. Prodding you. Working with and against you at the same time. Battling the climbs and the elements at pretty much the same time as you. So many things play a role, and there is no silver bullet to solving the problem.

For those very same optimists, I asked, what made them think that it could be done. For each rider, the response seemed to be yes, except for one outright no. (that rider talked himself into it later). One response was that “anything was possible” — IF — you had all the right conditions. “With the right combination of riders weather conditions” I was told by Bill Ash “I don’t even think it would be that big a feat”. But how hard is it to get that right combination.

Ricardo Pichetta was less optimistic about that combination. “I think it is not possible, at least in our amateur category, where there are no real teams able to manage the race for at least 70% of the duration.” This was an interesting thought — 70% of the duration (70 miles, and most of the tough climbs), to Pichetta, means a group that is organized and making the same hard effort. He continued “…with mates completely at the service of your captain, they can keep a higher pace, a constant pace, for a longer time, and then try to get to the goal, but, without a team, organized that way, I see it as very difficult.” Picking at the scabs of Pichetta’s doubts, he was clear that this race doesn’t unfold as he described. “In the year in which I raced (GFNY in NYC — 2017), in the last 50 km there are about 20 athletes, most of them singles, and everyone tries to save as much as possible for the final kilometers. The race is slowed down due to fatigue, to the difficulty of the final part of the course, to individual tactics, and the desire to win.” Puts a little bit of a damper on the optimism. But it qualifies Gabriel Corredor’s opinions about the individuality of the efforts along the way. According to Corredor “OK the biggest obstacles are the rivals! You can try to work together, four guys, or something similar, but someone will always catch the wheel, some work, some don’t and not everyone burns the same gas, and that can hurt your chances to complete the course in the necessary time.”

Providing an outsider view, someone who hasn’t yet raced the GFNY NYC Championship course, Matthias Van Aken compared the effort required to similar race course profiles he has done in Europe, where he has had the success of breaking four hours. “it will be my first time in GFNY New York, so I don’t know the course that well. I never rode on the roads before. I can tell you that I always ride by feeling, I never make a plan. If someone attacks early, I will need to follow or it can be over. So waiting till a certain point will not be a good idea. If I at least have a good sprint and attack on one of the last climbs — it is possible.”

Getting the Combination

Having an organized team was developing into a theme. To break four the approach would have to be thought out and everyone would have to know their role. According to Pichetta “If I had a team at my side of at least five or six athletes, I would try to involve them in some of the important stages of the race. Having them there in the initial part, so that I could stay calm and save energy, and then, in the final kilometers of the race, increase the pace to make as many selections as possible, and try to attack, obviously uphill where I have more chances.” So attacking the climbs. Working to your strengths. Letting the team get you there so that your energy is focused to exactly the portions of the course where you can create an advantage. But the climbs are the climbs are the climbs, and you are either a climber, or you are not.

Bill Ash, was conflicted about burning matches on the climbs to gain the advantage. “It’s a long race with a lot of climbing that doesn’t lend well to recovery. The climbs that come after Bear don’t have long high-speed descents. They’re short. Meaning, how fast you go up and over the top is more important than the speed you carry going down the other side. The back side of the route really requires a hard even steady effort. Torch yourself on anyone of those steep pitches after conquering Bear and you won’t stand a chance.”

With that said — Pichetta has yet to test what it would be like on the climbs without a team. “Unfortunately I have always raced alone in NY, without teammates, let’s say that past experience has served me to be able to identify athletes who could be my allies of the day etc., if I had a team certainly, I would clearly raise the rhythm from the ascent of Bear Mountain to the rest in returning to the finish line.”

Van Aken is predicting his own pain in the upcoming race, but it will not lessen his intent to break four, and without a team will be relying on his conditioning to be his differentiator. “In New York I will be by myself, no teammates, nobody that will help me during the race. I don’t have mountains close to my house so I can’t train for the hilly part, but I have done this in the past as well during stage races, so I know I can climb hills without specific trainings. The only factor that I can control is my physical condition.”

Team or no team, at the end of the day, it’s all about one rider crossing the finish line in under four hours. The ability of that rider to handle the climbs is paramount. Ash felt that how to handle the climbs is an essential part of the strategy. “This is probably the biggest thing. This would be relatively benign feat had you not had a big climb (roughly 10km and 500m) right at the halfway point (Bear Mountain). For instance, if rather than going up and down Bear, that 2000 or so feet of elevation were spread across the first half of the course and 50 people could make it to the finish together — then it would be no problem. However, when you have terrain that makes the race so selective, that the front group shrinks to maybe 20–30 people with that much distance left to go, then that takes a lot of the inertia out of the group. You can’t really say you are going to slow down on Bear to get a bigger group over the top. And there are few people who could sustain that effort and then still be good for 50 miles solo. So, I think it will take a pretty selfless group of 10–20 riders to make it work.”

I think there is a name for a selfless group. Team?

Out of Our Control

It’s important to understand the team dynamic, and how using your energy in a focused way would be key contributors. But let’s remember — these are the things that are within the racer’s control. Anyone who raced GFNY in 2013 or has done a turn at second or third wheel, absorbing the spray of the wheel they are drafting knows that the weather can have an impact. And while it is probably the biggest in-competition factor that is out of your control, is it the only one?

Pichetta looks to the weather as a huge influencer on the ability to break 4 but also points to how the weather suits particular riders. “Surely the weather is a determining factor in the duration of the race, the rain would make the roads more difficult and the pace would be less, wind would help in increasing the pace of the race or facilitate progress, and certainly the athletes. There are athletes more suitable or less suitable for certain weather conditions.”

Ash agrees and adds even more weight to the weather as a factor but recognizes that the strength of an organized group is essential. “To be able to achieve something like this the weather conditions are everything. You could ride along at 500 watts for four hours and get nowhere if you’re getting blasted with wind the whole time. If you have a focused, coordinated group that’s determined to keep the pace high then that’s good. Lots of early attacks could turn the race negative unless it’s a big group that slips off the front. I think if enough people are motivated and the bunch rides the first half fast enough, then a small group could hang on and stick it to the end.” No doubt inspiring a showdown on the final stretch to the GFNY finish line festival.

With a little more pragmatism and continuing to pound physical condition and riding by feel, Van Aken was more worried about the mechanical perils, but recognized how the weather plays in his conditioning. “First of all, a flat tire! If that happens it will be very difficult to get back in the first group. And then the weather, cold and rainy weather is something I don’t like at all, the warmer the better for me! I am not scared about other riders; I just believe in my own strength.”

Not a Single Luxury

Stopping in this effort is tantamount to saying “I give up”. For most racers, it’s not inconceivable that you would stop to refill a bottle, take on more nutrition, or work out a leg cramp quickly before remounting and continuing on. (In some very wild cases, it is rumored that the entire Gavia Cycling team stopped for a coffee in the middle of a race in Italy once — but I wouldn’t know a thing about that). But this, this is different. This is a race for so much. A course record, the top step on the podium, and a cash prize of $10,000. COME ON!

There are none of the luxuries that you would find in watching the riders of the Tour or Giro take on water from the team car, or have a willing group of soigneurs on the side of the road holding musette bags full of food. There is no race radio. If you flat, or drop a chain, you break it — you bought it. You will need to see the gap to know how far it is. If you can’t see it, guess what, it’s too far. How will the riders contend with being full gas for the duration of the race?

“The support of a car or motorcycle gives you peace of mind in case of punctures and certainly of hydration and nutrition. Without that, we need to plan. The day starting early in the morning is not very hot, and I’m not a big drinker, this helps all participants. All the more so in the head of the race where we do not stop at the aid station…” says Pichetta “…for me, 4 mini sandwiches with jam and 2 isotonic SIS gels in the most nervous phases of the race, then counting on having 2 bottles of natural water and a drink that replaces solid food, in the decisive race stages.” Those five GFNY jersey pockets will certainly come in handy.

Ash feels that there will be better luck being at the front with not needing to stop (outside of mechanicals). “My first GFNY in 2017 I spent a lot of time by myself off the front, and due to the amazing volunteers was able to get hand ups pretty easily. If it’s a mild day two big bottles is not ideal but could get you through it. However, if it’s anything like the last two years *fire emoji*.” His optimism continued in his ability to find the right soigneur. “My girlfriend is also under the impression that this should be something that is easy to do and will pay for her engagement ring — so maybe she might be willing to stand out on the side of the road with a musette bag or something.” Hmmm, maybe those five jersey pockets are a better bet.

Making the Big Move

Every race has one. It’s memorable, for the winners and the losers alike. That moment that will be looked back on as the race-changer. The moment of “I should have”, or the moment of “I sure am glad I did”. So how do these racers know when it’s time. Crossing in under four is one thing, but if you are going to do it, you will only bring home the bacon if you do it first. So how do you keep Mr. Wheelsucker from stealing your coin, and your podium spot? “The last 15 km, I have 70% in my favor…” says Pichetta, “…ascents, not too demanding but after the long day can be decisive. If I had a team and then in the final kilometers with one or two team mates, I would raise the pace in the last 15 km, in the last climbs, and I would try to attack about 4km from the arrival. This is where I had attacked when I won the race in 2017.”

Van Aken was more about feel, as he had been with much of the topic. “I don’t know how hard the climbs will be, so I will be racing by my feeling, if I feel good it’s possible I will try something on the last hills or I will wait until the final sprint.” Assuming that he is in a pack of contenders at the final kite. “My biggest goal is to have a good race, with a nice result and who knows in less than 4 hours.”

For Ash, the move is simply to “dive bomb the last corner to get to the front of the pasta line” if that isn’t worth $10,000 after breaking four hours — I don’t know what is. But hey, if that’s the move, he might consider a different strategy for that engagement ring.

The Takeaways

Well if I had to sum it up, the secrets seem to be a good team or organized group. Great weather (working on it), managing the climbs, keeping on top of your nutrition, and finding the right spot to make your move. Wow — it’s kind of like the advice for having anyone’s best GFNY, only faster! I will admit that when I first saw the poll, I was a hard “NO”. I didn’t think it could be done. The outright cruel brilliance of the course, I felt, was prohibitive enough to stop anyone daring enough to try. Reading this back to myself, I know, now, that someone will do it. So here goes my prediction. The winning time at GFNY Championship NYC 2019 — will be 3:52:10. I reached out to every contender that I could find to ask the questions, and while I found truth and wisdom in the words of those who replied, I found something more in the silence of those who didn’t. The race is on, and there are some who would rather not share their strategy or their goal. They will no doubt reveal themselves, that third Sunday in May — right around 10:52:10 AM Eastern Time.